Trompe l'oeil murals

This article originally appeared as Painted facades and public memory, in Context 147 published in November 2016 by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation. It was written by Dennis Rodwell.

[Above: House mural, Glenelg Road, Brixton]

As a visually dramatic means of story-telling, large-scale murals can be an effective way to engage communities and communicate public memory to multiple audiences.

Recent decades have experienced the revival of centuries-old European traditions of painting the facades of buildings both for decorative and narrative purposes. These latter, especially using techniques of trompe l’oeil, provide a highly effective medium for animating plain, individual walls and whole quarters of cities, and for engaging in a multitude of ways with citizens and their communities through participatory origination and story-telling.

Depictions may interpret archaeological finds, celebrate people and historical events, record urban transformations both actual and unrealised, or portray futuristic visions. Operating at a neighbourhood scale, they can perform a vital role in urban regeneration: respecting the inherent sustainability of existing built environments and their communities; reinforcing sense of place, social and cultural identity and civic pride; and providing an exceptional canvas for public art that evokes and stimulates collective memory.

Heralded as a world leader, CitéCréation (formerly Cité de la Création) [ref 1], a cooperative of muralists established in the Lyon metropolitan region in 1978, has originated over 650 mostly large-scale frescos in cities across Europe, the Americas, and the middle and far east. Lyon itself, ‘the capital of painted walls’, now boasts numerous examples of what has become a fundamental part of the city’s town planning and urban communication. In this, the specific characteristics of the city’s various districts and neighbourhoods have served as the basis for expressing and celebrating their discrete identities.

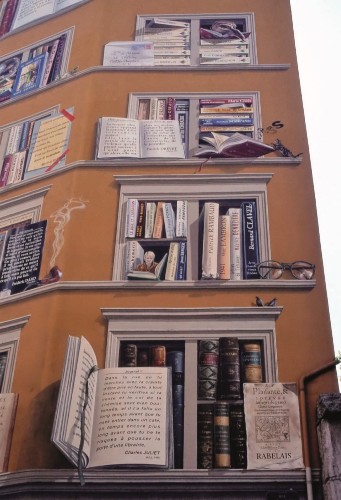

Thus, historical associations and cultural life are celebrated in the city centre, and the city’s historical roles in the silk, printing and transport industries, pioneering role in cinematography, prominence in gastronomy and viticulture, and contemporary role as a centre of innovation in the artificial fibre, software and other emergent industries, all find visual interpretation across the city.

Lyon is also a prominent city of sport. Following the French national team’s victory in the 1998 football world cup, a celebratory fresco was created on a blank tenement gable wall facing the Gerland stadium and sports’ complex. Further, the fresco of Shanghai marks its twinning with the Rhône-Alpes region, of which Lyon is the capital.

|

|

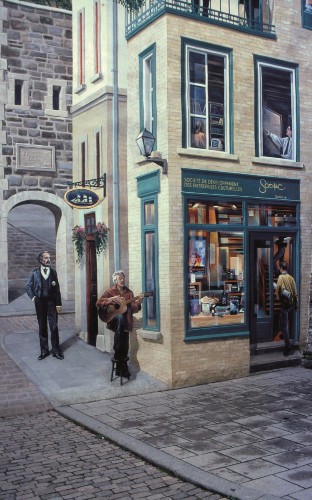

[Left: Quebec City, Canada: a detail of the fresque des Québécois, tracing 400 years of the city’s history.]

[Right: Lyon, France: an urban fantasy fresco.]

The legacy of Tony Garnier, visionary architect-planner and native of Lyon, acclaimed especially for his elaboration of une cité industrielle (an ideal industrial city), is represented in the ‘Tony Garnier Urban Museum’: 25 frescos covering 5,700 square metres on gable walls in the Quartier des États-Unis – the inter-war social housing district designed by Garnier. This open-air museum was incorporated into the 1980s-to-1990s regeneration programme for the district, championed by the tenants’ association as an essential component of the vision to enhance the district’s image within the city and promote awareness of its heritage value to wider audiences.

|

|

[Left: The fresco ‘The City Library’ at Lyon.]

[Right: Lyon, France: the Gerland fresco next to the city’s sports stadium and, in the foreground, one of the city’s many Vélo’v bicycle-sharing stations.]

CitéCréation has also worked in Quebec City, on murals celebrating the city’s long history and the manifold craft trades and skills of its early French settlers. Murals by others can be found throughout Europe, such as the historical narrative portrayed on a wall in the old town of Bamberg.

This type of public art requires both initial impetus and long-term commitment. CitéCréation is a public private partnership that relies heavily on sponsorship. Murals are not one-off art works. They depend on the stability of their substrates, and deteriorate through seasonal weather patterns and fading. Periodic renewal, on a 10-to-15-year cycle, must be programmed in. This requires strong partnerships at all levels: from enthusiastic citizen involvement in their subject origination and design; through political support in the strategic and detailed planning system; to continuing management and financial commitment.

Lyon has extended its positive experience with public artworks into other facets of the urban infrastructure. The city is also noted for operating Vélo’v, the first successful public bicycle-sharing scheme in Europe. Established in 2005 in a cost-neutral partnership between the city and the advertising company JCDecaux, variants of Vélo’v are now a familiar sight in many European cities.

In the UK, public art in the form of sculpture is a more familiar sight: costly, but one-off; of direct visual impact and tactile when close-by, but lacking in the drama and visibility of large-scale frescos.

Dundee, for example, was famous for its ‘three Js’ – jute, jam and journalism. The publisher DC Thompson is renowned for The Dandy and The Beano, two children’s comics of which the latter continues in publication. Demonstrating that culture is inclusive across genre and generations, the bronze ensemble with Desperate Dan (from The Dandy) is a main feature in the pedestrianised High Street.

[Dundee, Scotland: a bronze ensemble of the comic strip characters Desperate Dan, Dawg and Minnie the Minx by the artists Tony and Susie Morrow.]

My own direct induction into the world of urban-scale murals occurred in the early 1980s, as architect for the upgrading and repair of late-19th-century tenements in Milton Street, Edinburgh, a cul-de-sac immediately to the east of the Palace of Holyroodhouse and backing on to the royal park. It was from there that James Tyler, a Scottish chemist and inventor, made Britain’s first hot-air balloon flight in 1784, less than a year after the first manned flight in Paris (in a balloon designed by the Montgolfier brothers). To commemorate the bicentenary in 1984, a proposal was researched and formulated to place a mural on a highly visible gable.

One of my clients, a graphic artistic, prepared a visual, and a muralist was approached and estimates obtained. Although funding could not be sourced at the time, nor a mechanism for continuing maintenance and renewal, the lesson from this and later association with programmes of public art seems simple.

Large-scale murals are a visually dramatic means of story-telling that can have major benefits in terms of community engagement, and the communication of public memory to multiple audiences. One-off projects are very difficult to promote, let alone maintain. When, however, they are framed in the context of urban-scale projects that capture the imagination of citizens, coupled with widespread political, professional and financial support, they can make a significant contribution to enhancing and sustaining our built environments, whether or not they are regarded as historic.

|

|

[Left: Tarragona, Spain: a three dimensional projection of the Roman Circus on a gable overlooking the archaeological site]

[Right: Tarragona, Spain: a trompe l’oeil mural in the Plaça dels Sedassos celebrating popular local traditions by the artist Carles Arola]

Dennis Rodwell, an architect-planner, is a consultant in cultural heritage and sustainable urban development.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- A brief history of graffiti and the built environment.

- Art in the built environment.

- Bas-relief.

- Blind arch.

- Conservation.

- Fresco.

- IHBC articles.

- Kinetic facade.

- Listed buildings.

- Mosaic.

- Moulding.

- Nuclear Dawn mural, Brixton.

- Paint.

- Rendering.

- Rustication.

- Stained glass.

- The Anatomy of Colour.

- Tessera.

- Trompe l’oeil.

- Wallcovering.

External references

[1] See also ‘Picking up the threads in Lyon’, Context 106, September 2008, and ‘Signs of a revitalised, more relevant, ICOMOS’, Context 107, November 2008

IHBC NewsBlog

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.

IHBC Publishes C182 focused on Heating and Ventilation

The latest issue of Context explores sustainable heating for listed buildings and more.